Coming from part one and two of this series, let’s try to figure out why the unified European currency has been leaking, and was never fixed.

So, why on earth isn’t the EU capable of sustaining raising interest rates without breaking itself apart?

Good question. I’m going out on a limb here: I live in Italy, and I have my view, and that makes me see one of the roots of this problem with a very specific angle. I could be talking about it for ages. But I want to project a more unified outlook of it, so let’s say that maybe, just maybe, this is the reason why:

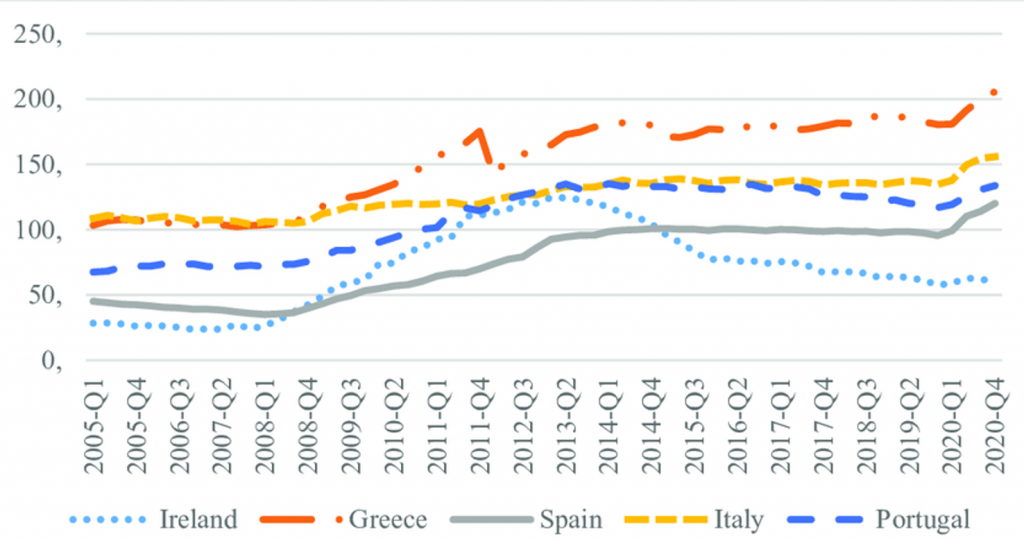

The infamous PIIGS acronym is there for a reason

PIIGS or its updated revision one letter shorter, is a shameful acronym. I don’t condone it. But it’s there for a reason. Those are the EU countries with the most outstanding sovereign debt compared to their GDP. Those are the countries which most often are underperforming against the rest of the pack. And those are the countries whose debt service cost increases dramatically:

| Observed condition | Occurrence |

| when a rate hike is attempted | which is seldom |

| when some political instability manifests | which is often |

| when some other factor causes economic or commercial concern | basically all the time |

| or for no good reason at all | does not apply |

Some countries within the eurozone are on their merry way to bankruptcy. There is no other way to look at it, I’m sorry. I’m currently in Italy, and we are eyeing the passing of the 160% debt-to-GDP threshold, all while the political landscape is fighting tooth and nail to secure all the necessary steps in order to recede even more. It’s insane.

Let’s take Italy, for example.

At the time of writing, the amount of pressure from the maintenance of this unfathomable amount of debt is actually not that high. Overall fiscal pressure in Italy of course is off the chart, but the debt servicing component is still manageable.

But this in turn means that, should the ECB perform some serious rate hike, the resulting debt servicing costs on the Italian economy would make things spiral out of control so fast you can’t even see it.

The nation enjoys a relatively high sovereign bond rating, which makes borrowing money still the first (and only) course of action. But here is the catch: it’s a one-way road. Italy is nowhere near being in shape to reduce its debt.

There is simply no way the country would take the necessary steps to generate surplus and cover for some of its debt. It’s not going to be accepted, not at the political, nor at the societal level. Italy’s economic viability subsists entirely on it being able to emit more debt at every bond maturity date. In other words, sovereign debt servicing MUST continue being cheap, long-term, in order for Italy to remain solvent, just a little longer.

Kicking the can is far easier than kicking cocaine addiction.

Having access to perpetually lenient debt markets is a condition that the country has hardcoded and entirely discounted into its internal workings since joining the Euro area, and has its roots into the deficit splurge of the ’70s when the country was growing at a double-digit pace. A reality view that sadly was never really revised. Regardless, the country today is hopelessly dependent on this premise and – mark my words – there are no sustainable devices that the country can willingly adopt to reduce its debt.

Italy has consistently underperformed almost any other country during the years, and considering its bleak outlook when it comes to its financial debt policies, I’m going to ask a simple question: should any rating agency ever rank Italian debt as investment grade?

The only reason Italy, or most of the PIIGS countries, are getting away with it, is the ECB perpetual PUT being in place. Therefore the easy money faucet can’t be closed. Ever. Not gonna happen.

There you have it, this is the origin of the leak of value priced in the EURUSD chart.

And that explains why on earth the ECB is always found with its hands tied at the most inappropriate times. A real, serious rate hike would put the mechanism in motion for a downgrade of some PIIGS sovereign debt, something that would break the union apart in all practical terms.

The failing EUR>USD axiom

Now, meet the US Dollar Index. It mirrors the EURUSD decline perfectly and, being a good 30% in the green, today it seems ready to give away some gains. It actually bounced back after its recent all-time-high of almost 13200.

Maybe I’ll write a post on how to play this trade. [UPDATE: I wrote this post!]. But regardless, this bounce saved EURUSD from closing below the psychological threshold which is the 1.0 parity. Make no mistake: this was intentional.

Yeah sure, one might argue that the EURUSD parity level is an overpowering technical level at which trade positions, after such a long ride, begin to change sides. A level at which some kind of reaction was deemed to happen.

But the sad reality is that the Euro, being more scarce in terms of relative availability, has always outvalued the US Dollar, something which keeps being true since it started being widely circulated fiat money. I don’t think the market as a whole would profit from seeing this ratio broken to the downside. Euro has seen the market assuming EUR>USD for more than two decades now. It’s a hell of a lot of confidence which would be shaken, should said assumption suddenly cease to be true.

The EURUSD was simply prevented from closing below parity, for now. A market assertion which was respected by all involved parties. Institutions bought. Shorts covered, longs entered with the tightest stop loss on record. It somewhat worked. The important tidbit here being: for now.

The reason is simple. A decline below parity would result in an explosive move, the likes the currency would probably never recover. EUR=USD would then become a formidable resistance. And given the fact that the FED has the option of raising interest rates, while ECB really can’t, that would spell doom for the long term outlook of the pair.

But wait, here is the Spread Shield to the rescue!

ECB Anti-fragmentation Spread Control Tool or Whatever

Not all is lost, because with a full 12 months of delay, the ECB might have finally come to the realization that the unified currency is somewhat important, and that it can’t really be left to decay in value forever. So here it goes, talk of a possible less insignificant rate hike has spring up in the media.

A move that would make the EU bond market a slightly more competitive. In which if, say, Greece wanted to refinance its debt, it better make it worthwhile because on the creditor’s side that is a more risky investment than putting money in Dutch debt. And the deviation of national bond yields that is naturally born as a consequence, is the expression of that. I’m not saying it is healthy to have, or helpful. No. I’m just saying it is there for all the good reasons. It is a symptom.

So how do the ECB plans to placate the crazy bond spreads that are naturally born in the market each time a rate hike is announced?

But with the help of the mighty Spread Control Tool of course.

But what is it, after all?

Here is the kicker: everyone and their dog have been scrambling to understand exactly how this facility is supposed to work, and I personally have failed at that. Perhaps the ECB failed too, because the inner details still have to be announced. The feeling that they are going to make that up as they go is really, really strong.

Despite this, the intent of the device is to keep spreads under control.

I don’t need to be a genius to understand what this implies in financial terms. The market doesn’t need either. It’s pretty clear actually. Let’s look at the market reaction:

Clearly the market sees the bluff on the ECB part. The news has been interpreted as what it substantially implies: it’s QE Infinity, but with another name and some more paper constraints. Constraints that are supposed to entice the affected countries to make something good for themselves. Become more productive, improve their financial outlook. The good old carrot-and-stick model.

It is an old recipe. We’ve been there before. It doesn’t work in so many ways it’s almost embarrassing.

Let’s face it, the only way to control spread fragmentation between countries implies artificially making the most risky assets less competitive. Which means that the ECB will be buying them aggressively. This implies no end in sight for the balance sheet expansion and ultimately further dilution of the unified currency.

So what to make of all this? What is in for the unified currency? My personal take on the topic in the final part of this series.